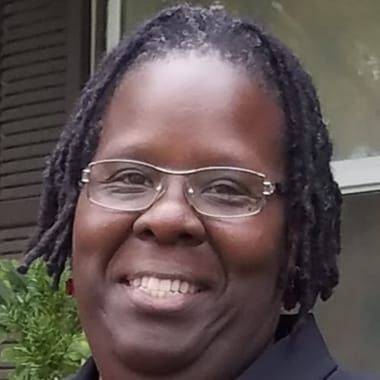

Dr. Anita Saunders is a 2013 TFA Indianapolis alumna and school psychologist at Indianapolis Public Schools.

Q & A

What are the biggest takeaways from your corps experience?

There are so many takeaways from my corps experience. I had never really planned on being a part of TFA, but once I was accepted, I knew it would be a life-changing experience. I was fortunate enough to be placed at Charles A. Tindley Preparatory School, an all-boys middle school at the time. There, I learned that education wasn't just about teaching a specific curriculum to a classroom of students.

Education is and should always be about the care of the whole child. If you don't care about your students while they are with you for a 45-minute lesson and the other times of the day and night that they are not with you, then why even teach? That seems like a lot to ask of one person who may have a family of their own; however, teaching was never designed to be an easy profession.

I also saw what I had known to be true: not every revolutionary educational model or theory fits every child. So many times, schools will say that their teaching methodology—be it accelerated teaching, use of technology, rites of passage ceremonies, or single-gender schools—is the key to student achievement. These CEOs, administrators, and researchers usually mean test scores, the arbitrary numbers used to determine if students, schools, and communities measure up to arbitrary standards set up by a society that never intended Black and brown students to meet them.

My greatest takeaway and continuing contribution is that there is no one-size method of education. As teachers, we must meet students at their levels and determine their individual needs to move them toward goals of their own choosing. We also must address the whole student, mind, body, and spirit. It is a lot to ask of one institution, but we need to think of educating children as the responsibility of every organization and citizen in our society.

How are you addressing educational inequity as an alumna?

My transition to teaching through TFA was an act of racial justice. Although I did not fit the typical demographics of a corps member, I knew, because of my own school experiences, the importance of having teachers who looked like me and shared a cultural background.

My mother attended segregated schools in Washington, DC, in the 1930s. She said all of her teachers were African American. She frequently tells stories of how her teachers possessed master's and doctoral degrees in their subjects and were only allowed to teach high school because their ethnicity prohibited them from securing university or industry positions. She told of how they scrounged around in university dumpsters for lab equipment and lived just a house down from their students, attending the same church and shopping in the same grocery stores.

Although my schools in DC were not segregated, I too had the fortune (or misfortune) of sharing a neighborhood with some of my teachers. I could be assured of seeing them Sunday mornings in church or Saturdays at the store, too. I had these shared identities and experiences in mind as I completed my TFA application. All students—especially Black and brown students—need to see themselves in their teachers. They deserve to have someone with a doctoral degree bring the breadth and width of their knowledge to the classroom.

After completing my tenure with TFA, I did not stop addressing racial inequity in education. I've continued my journey through conference panels, yearly workshops that I teach to educators, calling out and calling in teacher friends, and going back into the classroom (and soccer field) to be there for students to ensure that they continue to see themselves in their educators.

The inequities present in our educational setting will not be easily fixed or go away within my lifetime; however, I understand that I have a responsibility to continue to work toward deconstructing the barriers to equity while simultaneously constructing opportunities to create equity.